Welcome back!

We all knew the Age of AI would get weirder and weirder.

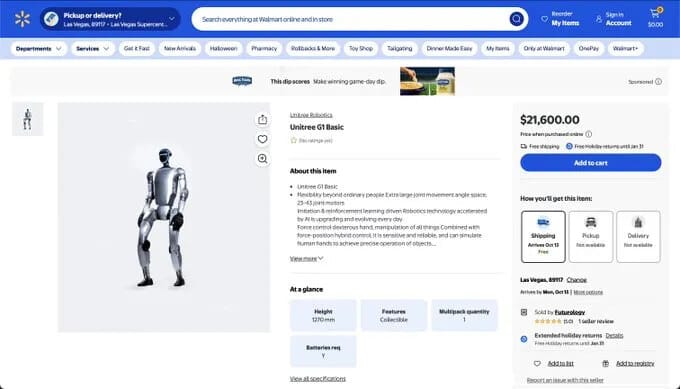

Now there’s an AI-generated “actress” making videos, talking to fans on “her” social media accounts, and generally freaking out all the real actresses and actors in Hollywood.

Lucky for us, AI-generated “people” — and their implications for art and society — are our bread and butter.

Click that button and keep at least one creative human employed.

Hollywood is in an uproar over an AI-generated “actress” that looks like a fresh-faced starlet who just got off the bus from Iowa, ready to make it big in the movies.

It’s a sign of how quickly AI has developed over the past few years that Tilly Norwood, as the avatar’s creators at Particle6 call it, looks so real.

Seriously, it’s shocking how much Tilly looks like a real person.

It’s also a sign of the times that Tilly’s creators could so easily plug her into a movie industry that already leans hard on computer-generated images to make mind-blowing special effects.

But the human actors in Hollywood have no intention of quietly allowing AI to take their place. They’re raising a ruckus about the threat AI poses to their livelihoods, and what AI portends for the future of art itself.

Meanwhile, movie executives are eyeing a super-cheap alternative to human actors, while stepping lightly to avoid violating the deal they struck with Hollywood unions to end a strike two years ago.

Is it art?

The actors’ union, known as SAG-AFTRA, has 160,000 members and they’re not happy.

The union issued a statement about Tilly, saying “creativity is, and should remain, human-oriented” and “audiences aren’t interested in watching computer-generated content untethered from the human experience.”

When a reporter at Variety showed Tilly to the actress Emily Blunt, she was taken aback.

“No, are you serious? That’s an AI? Good Lord, we’re screwed,” Blunt said. “That is really, really scary. Come on, agencies, don’t do that. Please stop. Please stop taking away our human connection.”

The founder of Particle6, Eline Van der Velden, said Tilly isn’t a replacement for art. It’s actually art itself.

“To those who have expressed anger over the creation of my AI character, Tilly Norwood: she is not a replacement for a human being, but a creative work – a piece of art. Like many forms of art before her, she sparks conversation, and that in itself shows the power of creativity,” Van der Velden said.

Tilly isn’t just a one-off idea from Particle6. They’re aiming big.

They created a sketch comedy video, generated entirely by AI, that works both as a launch of their AI vision, and a sly ribbing of the Hollywood establishment. It ends with the words, “But hey, at least it wasn’t a reboot.”

Is it theft?

That’s the question echoing not only through Hollywood, but other creative industries like music and books.

To build Tilly, developers at Particle6 had to train it on millions of hours of film and performances, all of which were created by real people who were never asked for their permission or paid to let their work be used to train an AI.

While AI companies tend to frame the process as “learning,” critics call it digital theft.

Beyond using a performance to train an AI, what happens when the avatar looks just like a real artist?

The debate over Tilly turned personal when Nashville musician Stella Hennen noticed that Tilly looked eerily like her.

Hennen never gave permission to use her likeness, and it’s not clear that Particle6 actually used her as the model for Tilly. But the resemblance is uncanny and Hennen started getting tagged by fans asking if she’d secretly gone digital.

Even if the debate over art vs. theft remains unsettled, there’s another big question to answer: Will audiences want to watch movies starring AI “actors”?

We have no idea.

But Tilly and her creators aren’t waiting around. They created social media accounts for Tilly, where she is already developing personal relationships with fans.

It didn’t come out of nowhere

Two years ago, during the Hollywood strikes, SAG-AFTRA made history by forcing studios to address how AI would be used.

The union’s final deal with the studios — after months of shutdowns — included some of the first-ever guardrails around digital likeness and voice replication.

Actors won the right to consent before their image could be scanned, stored, or reused by AI systems, and to be paid if their digital doubles were deployed in future productions.

But those guardrails dealt with studios using AI to recreate the likeness of specific, human actors. The deal didn’t ban the creation of “synthetic fakes” that aren’t based on real actors or are made from a composite of many actors.

At the time, it felt like a landmark victory.

But as tools like Tilly and AI-generated video platforms surface, it looks like that victory might be short-lived.

Going forward, the actors’ union might find some inspiration in the publishing industry.

Last month, the AI company Anthropic agreed to a $1.5 billion settlement in a class-action lawsuit brought by authors and publishers who claimed their books were used, without consent, to train the company’s AI models.

The case, Bartz v. Anthropic, centered on data scraped from pirate libraries and alleged widespread copyright infringement.

While the settlement didn’t set a formal legal precedent, it sent shockwaves through the industry.

It was the first major acknowledgment that training data has value, and that the people behind it deserve to be paid.

The deal includes payments to eligible rights holders, with claims due by March 2026, and has already pressured other AI companies to reexamine how, and from whom, their models learn.

AI meets the Almighty: A new app called Text With Jesus lets people message biblical figures like they’re in a group chat from heaven. Ask Moses about patience, and he’ll text you scripture — powered by ChatGPT. The app’s gone viral with thousands of users and glowing reviews, as curious believers turn to AI for daily devotionals. But the pushback’s loud, too — pastors call it “digital blasphemy,” and theologians warn it’s turning faith into fan fiction.

NeuroChat reads your mind: MIT’s new chatbot doesn’t wait for your words — it listens to your brain. By tracking focus and curiosity in real time, it adapts how it teaches and talks, making every chat feel more human. Researchers call it “neuroadaptive AI,” but it’s basically mind-reading for better conversation.

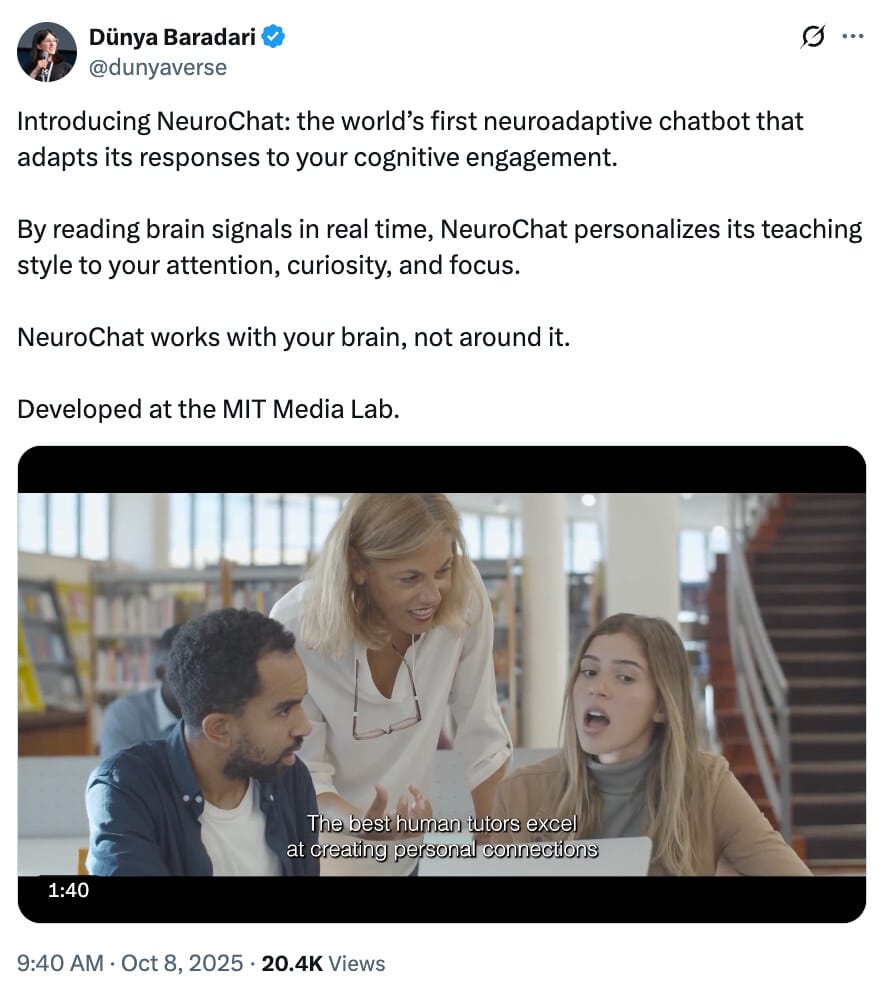

Robots for sale: Walmart started selling Chinese humanoid robots a few days ago, and the news quickly went viral. It took Walmart two days to take down the postings, but it’s still a big step in the world of consumer robots.