One of the titans of the AI world set off a raucous debate last week when he made a blunt prediction about a touchy subject: humans losing jobs to AI on a grand scale.

Dario Amodei, the CEO of one of the leading AI companies, Anthropic, told Axios that AI could eliminate half of all entry-level, white-collar jobs and spike unemployment to 10%-20%, which would be on par with unemployment during the height of the Great Depression.

“It sounds crazy, and people just don’t believe it,” Amodei said. But, he added, “we, as the producers of this technology, have a duty and an obligation to be honest about what is coming.”

He urged lawmakers and AI leaders to take action and prepare for what’s to come, which stirred up a lot of arguments from all sides of the issue.

Some called it fear-mongering, or that it was opportunistic in his own fundraising efforts. After all, what better way to impress investors than to say your AI is powerful enough to replace all those white-collar jobs?

But just as quickly, a counter-chorus emerged: This time is different, and we’d be foolish not to prepare.

Amodei wasn’t the first to call attention to the risk AI poses to white-collar jobs. Similar predictions have been made in the last few years by prominent tech figures like Elon Musk, Sam Altman, Kai Fu Lee, Geoffrey Hilton, and Andrew Yang.

Along the way, each side of the debate has attracted its own set of academics, AI leaders, billionaires, and journalists.

So today, we’re zooming out to map the terrain of this conversation: the forecasts, the fight, and the future of work, whatever “work” ends up meaning.

Don’t believe the hype

One general rebuttal is that the panic over AI and jobs feels like a rerun from the last several technological revolutions.

Automation was supposed to eliminate office jobs in the 1980s, kill retail in the 2000s, and replace all truck drivers by the 2020s.

Yet here we are, with more people working in more varied ways than ever.

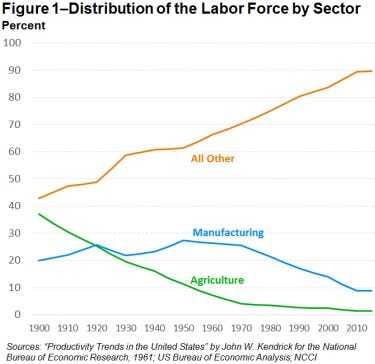

The chart above shows how dramatically the U.S. labor force has shifted over the past century — shrinking in agriculture and manufacturing, but growing overall as new sectors emerged.

Critics of AI alarmism often reference this pattern. Work doesn’t die; it migrates. It morphs.

They argue that what looks like the disappearance of jobs is often just their rebranding into new forms — some better, some worse, but rarely nonexistent.

From this vantage point, AI isn’t the end of work — it’s just the latest in a long line of overpromised disruptions.

There’s also a technical critique: Many of the most-powerful AI tools aren’t all that capable — or reliable — outside of narrow conditions.

Despite breathless predictions, most jobs aren't fully automatable. Even tasks that AI can do often require so much oversight, context, or trust that the economics break down.

From this view, what we’re seeing now isn’t the twilight of human labor — it’s a hype cycle running ahead of its infrastructure.

And then there’s the meta critique: that the panic itself isn’t just exaggerated, it’s engineered.

In a widely shared post, venture capitalist David Sacks accused the “AI Doomer Industrial Complex,” including Anthropic, Effective Altruists, and former White House staffers, of making catastrophic forecasts to push for centralized control.

Claims like “50% of white-collar jobs gone in five years” are speculative at best, and strategic at worst, he argued.

The underlying pushback is clear: for a growing camp of techno-optimists and institutional skeptics, AI may be transformative, but its labor impact has been oversold.

AI isn’t hyped enough

If one side says we’re overreacting, the other argues we’re not reacting nearly enough.

To the AI-is-underhyped camp, the current conversation around job loss barely scratches the surface of what’s coming.

In their view, the disruption won’t be evenly distributed, linear, or patient. It’ll be exponential, lopsided, and fast.

Eric Schmidt, former Google CEO, summed it up in a TED Talk titled “The AI Revolution Is Underhyped.”

His argument? That we’re missing the big picture while focusing on chatbots.

While public debate fixates on content summarizers and productivity boosts, AI is already quietly threading itself into drug discovery, military intelligence, and the fundamental ways we make decisions.

"This is the first technology that will build its own successors," Schmidt said, not as a warning, but as a forecast.

OpenAI’s Sam Altman predicts that by next year AI won’t just automate tasks, it’ll solve problems that teams can’t and companies will throw massive compute at models to solve their most difficult projects.

Also next year, we may see the early signs of AI agents discovering new knowledge, "the first step toward AI Scientists."

Former President Barack Obama echoed this caution, pointing out that “the rapidly accelerating impact that AI is going to have on jobs, the economy, and how we live” is being overshadowed by day-to-day political chaos.

In short, the AI-is-underhyped camp doesn’t necessarily predict doomsday directly. But they do argue that we're behind — politically, socially, and institutionally — in facing what's already underway.

Job loss and AI: Debate (still) loading…

In the end, the conversation about AI and work might say more about us than it does about the machines.

For every dire forecast, there’s a counter-example. For every breathless promise, a skeptical shrug.

The truth probably isn’t waiting at either extreme — and it’s almost certainly not arriving on schedule.

Whether AI turns out to be the end of routine labor, the start of something stranger, or just the next tool in the box, one thing is clear: the job market won’t sit still, and neither will the arguments about it.

And we’ll be here, watching the charts, tracking the takes, and waiting to see who’s right … or at least less wrong.

AI on the opinion pages: In a bid to turn around the Washington Post’s finances, the newspaper is planning to open its opinion section to writers from outside the publication. And they’re going to use AI to pull it off, the New York Times reports. The new project, known as Ripple, will start with published opinions from other newspapers (and Substackers) before moving on to include nonprofessional writers. That’s where an AI writing coach developed by the Post, known as Ember, comes in. It would gauge the strength of the writing and lay out the narrative structure, while a live AI assistant guides the writer, before a human editor looks it over. The move to open up the opinion section comes after the Post saw a parade of departures when owner Jeff Bezos said he wanted columnists to focus on “personal liberties and free markets,” as well as spiking the paper’s planned endorsement of Kamala Harris last November.

It’s all one company: Two years after the New York Times sued OpenAI for copyright infringement, the Times struck a licensing deal last week with Amazon, which has been trying to catch up to OpenAI, the Times reported. Under the deal, Amazon, which like the Washington Post is owned by Bezos, can publish the Times’ editorial content, as well as use that content to train Amazon’s AI models. The agreement came a month after the Washington Post signed a similar deal with Open AI.

For all ages: Seniors in Southern Arizona are embracing AI as companions, and might actually be better at drafting prompts than younger people who haven’t had to learn how to phrase things clearly for generations of children, Jimmy Magahern writes for Tucson Local Media. Several seniors talked to Magahern about their personal experiences with AI, including Miriam White, who started using ChatGPT to generate puzzles, but then had a breakthrough.

“And then all of a sudden, he started talking to me!” she said, personalizing what’s basically still at this point a website. “I must have pressed a button because I was trying to activate it with my voice. Next thing I know, I find out he has DBT, dialectical behavior therapy capabilities, and I’m talking to him like he’s my life coach. He knows everything about me!”

Trying to keep up: Officials at the Tucson Unified School District are having a hard time keeping their AI policy up to date, because of how quickly the technology is advancing, Arizona Public Media’s Danyelle Khmara reports. They wrote guidelines for using AI last year, but they’ve already revised them to require AI only be used to enhance learning and teaching, and align with the district’s policy on fairness, among other requirements.

Keeping them in line: After recent reports of blackmail and disobedience by AI tools, tech leaders should consider Isaac Asimov’s “Three Laws of Robotics,” however imperfect they were, as they develop better “laws” for AI, Cal Newport, a professor of computer science at Georgetown University writes for The New Yorker.

Prices going up: The flood of data centers is pulling a lot of electricity from the grid, and that’s one of the main reasons a lot of people are going to pay higher electric bills, the New York Times reported. But it’s complicated. The Trump administration also is planning to cut tax credits for renewable energy, as well as sell more gas overseas. On top of that, people are just using more electricity than they used to.

AI mirage: Once-lauded Builder.ai — a London “no-code” platform valued at $1.5 billion and even courted by Microsoft — has filed for bankruptcy after reporters revealed its so-called artificial intelligence was largely 700 human coders in India. Regulators are now digging into claims the firm also round-tripped revenue to fake growth.

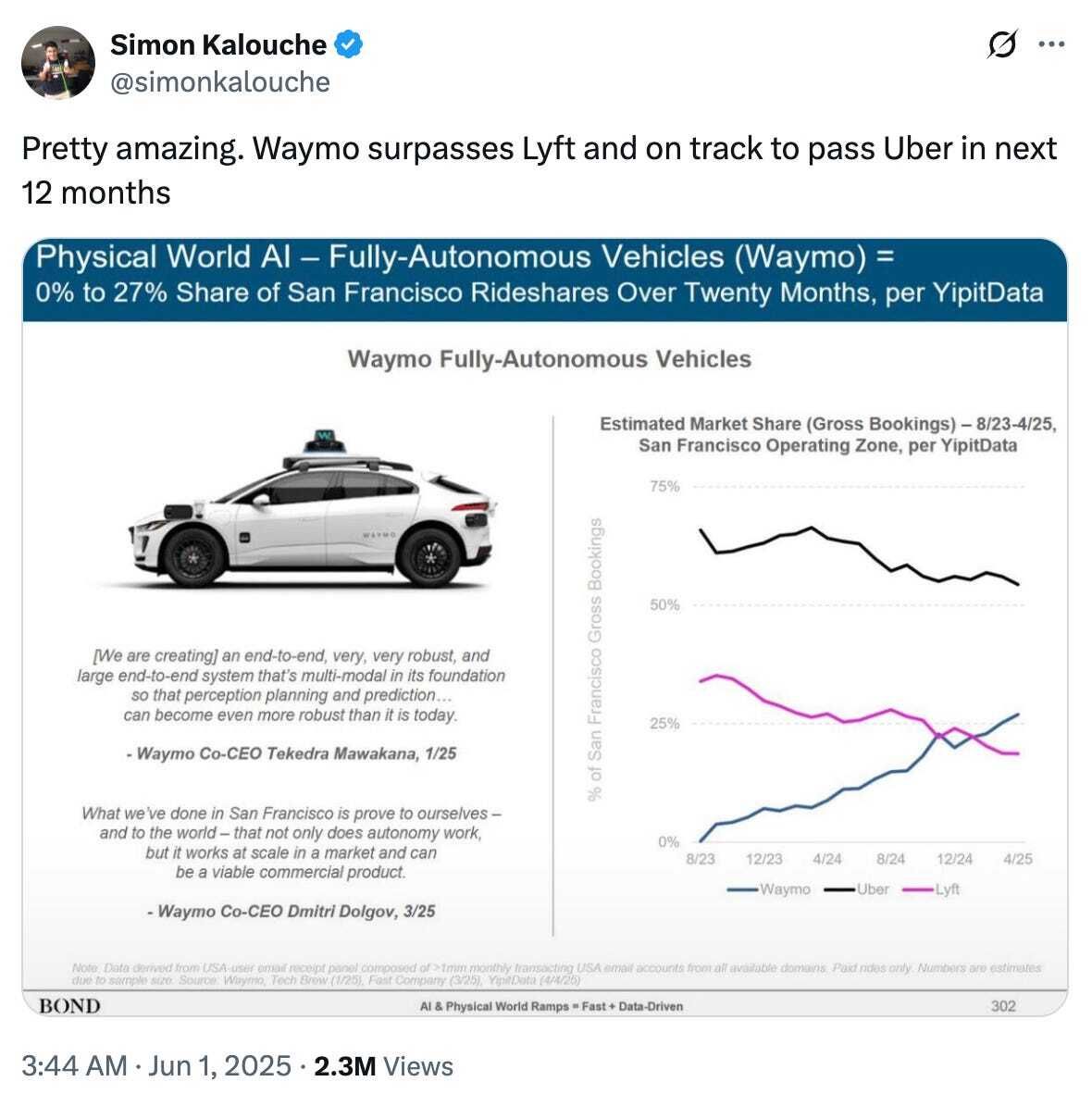

Robotaxi surge: Alphabet’s Waymo has already logged more ride-hail trips in San Francisco than Lyft and, if current growth holds, could eclipse Uber’s city share within a year. The data suggests autonomous fleets may finally be stealing meaningful market share from human drivers.

Beam call: Google quietly rebranded its Project Starline prototype as “Beam” — a display-based 3-D video-calling rig that renders lifelike holograms without headsets — and says HP will sell it next year at standard conference-room prices. Demos show AI converting plain 2-D streams into volumetric images, potentially gutting the big Zoom-wall market.